We are travelling north to Amsterdam from Paris. It’s still dark outside at 7 am, which makes it hard to tell when we’re underground and when we aren’t. The train glides at 250 km/hr comfortably enough for mon cherie to shut her eyes briefly, until we’re interrupted by the mustachioed man who check our tickets. Occasionally another train travelling in the opposite direction whips by, a flash of gleaming windows that disappears in less than a quarter second.

It’s been four intoxicated, caffeine-fuelled, jet-lagged days since we arrived in Paris on an early Saturday morning. The drive in from the airport reminded me of home. The highway looks like the Gardiner Expressway coming into Toronto off the QEW. Amid the illuminated billboards and concrete overpasses the only clues that we are in Europe, besides the unshaven Corsican cab driver who continually snorts back great gulps of snot in between exclaiming the virtues of this “number one city”, are the circular speed limit signs: 110 km/hr. That, and the fact that Parisians appear to obey.

The first real sign that we’re here is as distinctive as it is hard to describe, when you first see it in real life: the Eiffel Tower. The Eiffel Tower – le Tour d’Eiffel as its called here – looks different at different times. It’s changing moods reflect the diverse nature of this city, its inhabitants and their history.

In the early morning it is cool, calm and reserved, like the self-possessed Parisian who ignores my excusez-moi‘s as we struggle to find our way in this maze of a city. I’ve learned two things about navigation here. The first is that maps are useless, because even if you do manage to find where you are on a map after emerging like a sun-blinded gopher out of the subway, it’s impossible to determine direction and the street intersections and signage are impossibly confusing. The second is that Parisians have no clue where anything is either – or they simply don’t care to tell – so asking them is pointless too.

During the day, the view of the Eiffel Tower makes it no surprise that Parisians were first widely opposed to it when it was completed as the entrance arch for the Exposition Universelle in 1889: it’s enormous bulk is monolithic, imposing, impressive in an intimidating, gothic way. To me it looked like an armoured fist covered in spikes jutting into the sky, a defiant exclamation of French pre-eminence. Built to celebrate the French revolution when democracy triumphed over the monarchy, it’s jagged strength evokes imperialism as much as it does pride in the triumph of the people.

This conflict of human nature is everywhere in the architecture of Paris. In the shadow of the Eiffel’s iron fist, hundreds, perhaps even thousands of Parisians lounge, smoke and play with their children in the park of the Champs de Mars, a long green park unlike any public space I have seen in Canada. People congregate here, their children running free – one little fellow pissed by the side of the path, his pants around his ankles as people walked by – and no one seems to be in a hurry. The gray concrete expanse of dowtown Toronto with its street meat vendors, sidewalks covered in chewing gum, and the bulbous Skydome is a very poor comparison.

The architecture here is truly incredible and impossible to describe, so I won’t. Seeing these buildings, many of which are related to government, makes me wonder to what extent the buildings themselves have shaped French history. Anyone who governs here must be filled with a sense of almost righteous certainty just from showing up at work. With such grandeur everywhere, it must be difficult to imagine policies that aren’t grandiose.

At night the Eiffel shines, by turns a shining golden beacon, then sparkling and flashing with white strobelights. Because a company installed a new light display a couple of years ago that they own the intellectual property rights to, its against French copyright law to publish photos of it taken at night. I promise to break this absurd law as soon as I am able.

If this were a travel guide instead of an account of actual experiences, now would be the time to eloquently describe the Paris nightlife, which legendarily sparkles as bright as the midnight Eiffel. Instead, as I found out the hard way, the City of Light might always be shining, but on late Sunday nights in October, its dead as a burned out flourescent tube.

We’d been drinking at our friends and gracious hosts Liz and Mark’s apartment for a few hours Sunday night, but whether I was holding back or had just gotten too used to it at that point, I didn’t feel particularly drunk. I had earlier announced my intention to take some photographs of the Eiffel at night and I was determined to do so. In the back of my mind I also imagined finding a happening bar, having a few pints, meeting some Parisians and having a wild-and-crazy time with my newfound friends.

Instead, after wandering a ridiculous distance down brightly-lit but utterly deserted streets, getting terrible directions from an enthusiastically drunk middle-aged couple (some Parisians are friendly), negotiating with a disgruntled gas station attendant for overpriced beer and getting more (possibly intentionally) bad directions, I found myself in a small brasserie eating stale popcorn, sipping a pint of 1664 (try saying that in French) and talking to a guy named Claude.

More accurately, I was listening to a guy named Claude. Desperate for human contact, I had tried to strike up a conversation with the visibly intoxicated bearded older gentleman at the bar. He spoke no English. Worse, he was convinced I understood French, because in the beginning of our “conversation” I had picked up on a couple words and responded somewhat appropriately.

That was enough for Claude, who proceeded to jabber at me for the next 15 minutes, as I went from sipping my beer to gulping it. I left after vigorous handshaking and heartfelt au revoir‘s and bon soir‘s from poor Claude, who I had deduced was lonely because his wife had left him, or he had never married, or he wanted kids but couldn’t have them, or his kids were over his head, a gesture he kept making. He was over my head too.

Now Paris is behind us. We’re pulling into Brussels, with Amsterdam ahead of us. “Casie looks really good”, she writes in my notebook. She’s right, as she is about so many other things. Thank you for that, Casie.

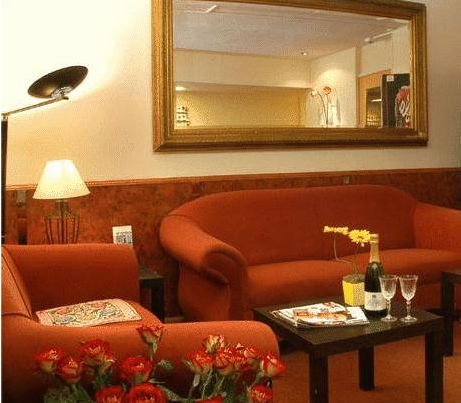

Classy. Elegant. Refined. It’s the Hotel Monopole, according to them.

Classy. Elegant. Refined. It’s the Hotel Monopole, according to them.

Not clean. Not pleasant. The Hotel Monopole, complete with wall closeup.

Not clean. Not pleasant. The Hotel Monopole, complete with wall closeup. Not clean. Not pleasant. The bathroom of the Hotel Monopole, with shower curtain closeup.

Not clean. Not pleasant. The bathroom of the Hotel Monopole, with shower curtain closeup.

twitter.com/adriandz

twitter.com/adriandz